for expert insights on the most pressing topics financial professionals are facing today.

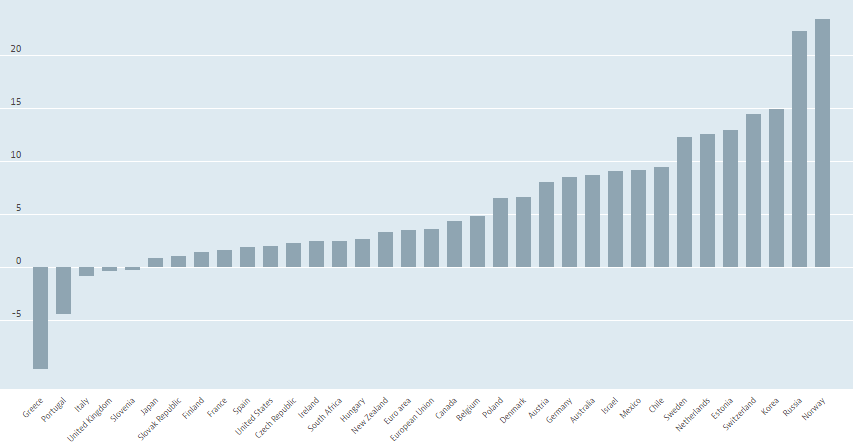

Learn MoreAmerica has a savings problem. According to a Gallup poll, 26% of adults have no savings set aside for emergencies, while another 36% have yet to start saving for retirement. And when comparing the U.S. to other industrialized nations, we fall far too close to the bottom of the graph, with an average savings rate of 2.0% of our annual GDP.

Savings data of the countries in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as compared to their annual GDP. Source: data.oecd.org

But economist Keith Chen thinks he might be able to help. In his Ted Talk, “Could your language affect your ability to save money?” he argues that our poor spending habits have a lot to do with the language we speak.

English, he explains in the 15-minute lecture, is a “futured” language. Meaning that English-speakers are forced to draw distinctions between the past, present, and future. As an example, he points to three versions of one event at different times: It rained, it is raining, and it is going to rain. In each version, it is clear that the event either happened, is happening, or will happen.

In many other languages however, such as Chinese or German, this is not the case. In those languages, which Chen refers to as “futureless,” there is no clear distinction between times. Translated exactly, these futureless languages would say the same three sentences as: yesterday it rained, today it rained, tomorrow it rained. In these languages, there is no distinction in time.

Basically, for “futured” societies such as ours, there is a clear distinction between the present and the future, which leads many of us to have a tough time imagining and therefore preparing for that future. For “Futureless” societies however, this distinction does not exist, allowing them to more easily empathize and plan for their future.

Which led Chen to a curious thought. What if our unconscious linguistic decisions had an effect on our financial decisions?

In examining a deep cache of household savings data from across the world, he found that where there exists pockets of “futureless” languages, there is also a spike in the average amount of household savings. Leading him to hypothesize that, by forcing the speaker to think of time in different ways, language works to either aid or impede a speaker’s ability to save money for the future.

Chen’s research is an intriguing blend of psychology, linguistics, and economics. But what implications does it have for English-speaking nations? Aside from learning a new language, what are we “futured” speakers to do?

He closes with this thought to give us hope: “Ultimately the goal, once we understand how these subtle effects can change our decision-making, is that we want to be able to provide people tools, so that they can consciously make themselves better savers and more conscious investors in their own future.”

As advisors, this is precisely what you do. You bring your clients’ future goals into the present moment; using the tools you possess – whether that is an online platform or your own intuition – to do so.

Hopefully now, you can do this with a bit more insight into why it is we Americans have such a hard time saving.